‘How I Learned to Fly’ by Orville Wright

Editor’s Note: Back in September 1914, Orville Wright told the world about his and his brother Wilbur’s airplane adventures in the pages of this magazine (when it was called Boys’ Life). Read the article below.

I suppose my brother and I always wanted to fly. Every youngster wants to, doesn’t he? But it was not till we were out of school that the ambition took definite form.

We had read a good deal on the subject, and we had studied Lilienthal’s tables of figures with awe. Then one day, as it were, we said to each other: “Why not? Here are scientific calculations, based upon actual tests, to show us the sustaining powers of planes. We can spare a few weeks each year. Suppose, instead of going off somewhere to loaf, we put in our vacations building and flying gliders.” I don’t believe we dared think beyond gliders at that time — not aloud, at least.

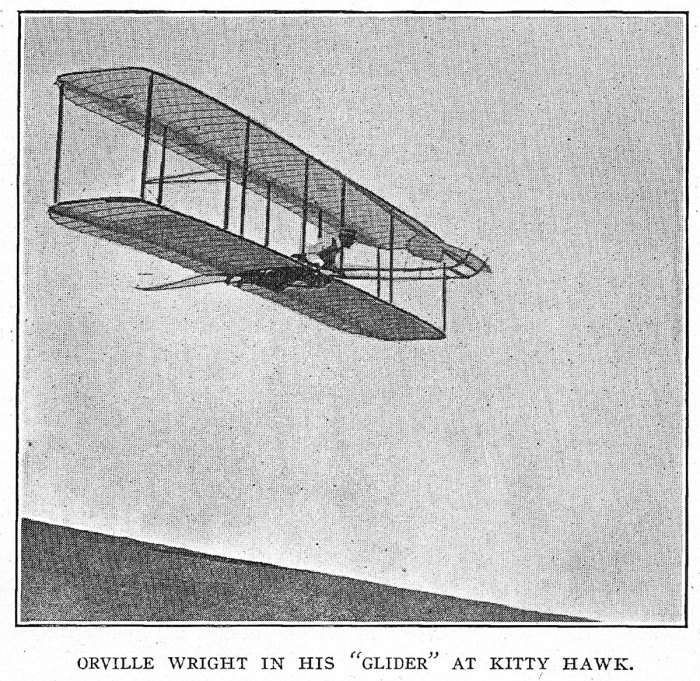

That year — it was 1900 — we went down to North Carolina, near Kitty Hawk. There were hills there in plenty, and not too many people about to scoff. Building the first glider was the best fun we’d ever had, too, despite the fact that we put it together as accurately as a watchmaker assembles and adjusts his finest timepiece. You see, we knew how to work because Lilienthal had made his tables years before, and men like Chanute, for example, had verified them.

That year — it was 1900 — we went down to North Carolina, near Kitty Hawk. There were hills there in plenty, and not too many people about to scoff. Building the first glider was the best fun we’d ever had, too, despite the fact that we put it together as accurately as a watchmaker assembles and adjusts his finest timepiece. You see, we knew how to work because Lilienthal had made his tables years before, and men like Chanute, for example, had verified them.

To our great disappointment, however, the glider was not the success we had expected. It didn’t behave as the figures on which it was constructed vouched that it should. Something was wrong. We looked at each other silently, and at the machine, and at the mass of figures compiled by Lilienthal. Then we proved up on them to see if we had slipped somewhere. If we had, we couldn’t find the error; so we packed up and went home. We were agreed that we hadn’t built our glider according to the scientific specifications. But there was another year coming and we weren’t discouraged. We had just begun.

We wrote to Chanute, who was an engineer in Chicago at the time. We told him about our glider; we drew sketches of it for him; we set down long rows of figures. And then we wound up our letter by begging him to explain why the tables of Lilienthal, which he had verified by experiments of his own, could not be proved by our machine.

Chanute didn’t know. He wrote back it might be due to a different curve or pitch of surfaces on the planes, or something like that. But he was interested just the same, and when we went down to Kitty Hawk in 1901 we invited him to visit our camp.

Chanute came. Just before he left Chicago, I recall his telling us, he had read and O.K.’d the proofs of an article on aeronautics which he had prepared for the Encyclopedia Britannica, and in which he again told us of verifying Lilienthal’s tables.

Well, he came to Kitty Hawk, and after he had looked our glider over carefully he said frankly that the trouble was not with any errors of construction in our machine. And right then all of us, I suspect, began to lose faith in Lilienthal and his gospel figures.

We had made a few flights the first year, and we made about 700 in 1901. Then we went back to Dayton to begin all over. It was like groping in the dark. Lilienthal’s figures were not to be relied upon. Nobody else had done any scientific experimenting along these lines. Worst of all, we did not have money enough to build our glider with various types and sizes of planes or wings, simply to determine, in actual practice, which was the best. There was only the alternative of working out tables of our own. So we set to work along this line.

We took little bits of metal and we fashioned planes from them. I’ve still a deskful in my office in Dayton. There are flat ones, concave ones, convex ones, square ones, oblong ones and scores and scores of other shapes and sizes. Each model contains six square inches. When we built our third glider the following year, ignoring Lilienthal altogether and constructing it from our own figures, we made the planes just 7,200 times the size of those little metal models back at Dayton.

It was hard work, of course, to get our figures right; to achieve the plane giving the greatest efficiency — and to know before we built that plane the exact proportion of efficiency we could expect. Of course, there were some books on the subject that were helpful. We went to the Dayton libraries and read what we could find there; afterwards, when we had reached the same ends by months and months of study and experiment, we heard of other books that would have smoothed the way.

But those metal models told us how to build. By this time, too, Chanute was convinced that Lilienthal’s tables were obsolete or inaccurate, and was wishing his utmost that he was not on record in an encyclopedia as verifying them.

During 1902 we made upward of 1,400 flights, sometimes going up a hundred times or more in a single day. Our runway was short, and it required a wind with a velocity of at least twelve miles an hour to lift the machine. I recall sitting in it, ready to cast off, one still day when the breeze seemed approaching. It came presently, rippling the daisies in the field, and just as it reached me I started the glider on the runway. But the innocent-appearing breeze was a whirlwind. It jerked the front of the machine sharply upward. I tilted my rudder to descend. Then the breeze spun downward, driving the glider to the ground with a tremendous shock and spinning me out headfirst. That’s just a sample of what we had to learn about air currents; nobody had ever heard of “holes” in the air at that time. We had to go ahead and discover everything for ourselves.

But we glided successfully that summer, and we began to dream of greater things. Moreover, we aided Chanute to discover the errors in Lilienthal’s tables, which were due to experimental flights down a hill with a descent so acute that the wind swept up its side and out from its surface with false buoying power. On the proper incline, which would be one parallel with the flight of the machine, the tables would not work out. Chanute wrote the article on aeronautics for the last edition of that encyclopedia again, but he corrected his figures this time.

The next step, of course, was the natural one of installing an engine. Others were experiments, and it now became a question of which would be the first to fly with an engine. But we felt reasonably secure, because we had worked out all our own figures, and the others were still guessing or depending on Lilienthal’s or somebody’s else that were inaccurate. Chanute knew we expected to try sustained flights later on, and while abroad that year mentioned the fact, so we had competition across the water, too.

We wrote to a number of automobile manufacturers about an engine. We demanded an eight-horse one of not over 200 pounds in weight. This was allowing twenty-five pounds to each horsepower, and did not seem to us prohibitive.

Several answers came. Some of the manufacturers politely declined to consider the building of such an engine; the gasoline motor was comparatively new then, and they were having trouble enough with standard sizes. Some said it couldn’t be built according to our specifications, which was amusing, because lighter engines of greater power had already been used. Some seemed to think we were demented — “Building a flying machine, eh?” But one concern, of which we had never heard, said it could turn out a motor such as we wanted, and forwarded us figures. We were suspicious of figures by this time, and we doubted this concern’s ability to get the horsepower claimed, considering the bore of the cylinders, etc. Later, I may add, we discovered that such an engine was capable of giving much greater horsepower. But we didn’t know that at the time; we had to learn our A, B, C’s as we went along.

Finally, though, we had a motor built. We had discovered that we could allow much more weight than we had planned at first, and in the end the getting of the engine became comparatively simple. The next step was to figure out what we wanted in the way of a screw propeller.

We turned to our books again. All the figures available dealt with the marine propeller — the thrust of the screw against the water. We had only turned from the solution to one problem to the intricacies of another. And the more we experimented with our models the more complicated it became.

There was the size to be considered. There was the material to be decided. There was the matter of the number of blades. There was the delicate question of the pitch of the blades. And then, after we had made headway with these problems, we began to scent new difficulties. One pitch and one force applied to the thrust against still air; what about the suction, and the air in motion, and the vacuum, and the thousand and one changing conditions? They were trying out the turbine engines on the big ocean liners at that time, with an idea of determining the efficiency of this type. The results were amazing in the exact percentage of efficiency developed by fuel and engine and propeller combined. A little above 40 per cent. efficiency was considered wonderful. And the best we could do, after months and months of experimenting and studying, was to conceive and build a propeller that had to deliver 66 per cent. of efficiency, or fail us altogether. But we went down to Kitty Hawk pretty confident, just the same.

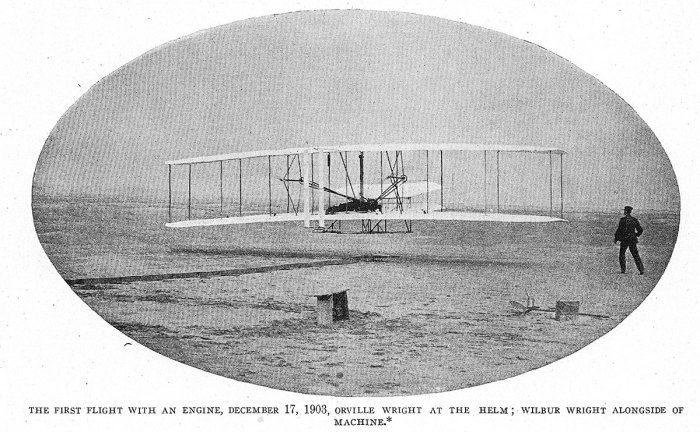

There were the usual vexations, delays. But finally, in December, 1903, we were ready to make the first flight. My brother and I flipped a coin for the privilege of being the first to attempt a sustained flight in the air. Up to now, of course, we had merely taken turns. But this was a much bigger thing. He won.

The initial attempt was not a success. The machine fluttered for about 100 feed down the side of the hill, pretty much as the gliders had done. Then it settled with a thud, snapping off the propeller shaft, and thus effectually ending any further experiments for the time being.

It was getting late in the fall. Already the gales off Hatteras were beginning to howl. So I went back to Dayton personally to get a new shaft, and to hurry along the work as rapidly as I could.

It was finished at last. As I went to the train that morning, I heard for the first time of the machine constructed by Langley, which had dropped into a river the day before. You see, others were working just as desperately as we were to perfect a flying machine.

We adjusted the new shaft as soon as I reached Kitty Hawk. By the time we had finished it was late in the afternoon, with a stiff wind blowing. Our facilities for handling the machine were of the crudest. In the past, with our gliders, we had depended largely upon the help of some men from a life saving station, a mile or two away. As none of them happened to be at our camp that afternoon, we decided to postpone the trial till morning.

It was cold that night. A man named Brinkley — W.C. Brinkley — dropped in to warm himself. He was buying salvage on one or more of the ships that had sunk during a recent storm that raged outside Kitty Hawk Point. I remember his looking curiously at the great frame-work, with its engine and canvas wings, and asking, “What’s that?” We told him it was a flying machine which we were going to try out the next morning, and asked him if he thought it would be a success. He looked out toward the ocean, which was getting rough and which was battering the sunken ships in which he was interested. Then he said, “Well you never can tell what will happen — if conditions are favorable.” Nevertheless, he asked permission to stay over-night and watch the attempted flight.

Morning brought with it a twenty-seven mile gale. Our instruments, which were more delicate and accurate than the Government’s, made it a little over twenty-four; but the official reading by the United States was twenty-seven miles an hour. As soon as it was light we ran up our signal flag for help from the life saving station. Three men were off duty that day, and came pounding over to camp. They were John T. Daniels, A.D. Etheridge and W.S. Daugh. Before we were ready to make the flight a small boy of about thirteen or fourteen came walking past.

Daniels, who was a good deal of a joker, greeted him. The boy said his name was Johnny Moore, and was just strolling by. But he couldn’t get his eyes off the machine that we had anchored in a sheltered place. He wanted to know what it was.

“Why, that’s a duck-snarer,” explained Daniels soberly. North Carolina, of course, is noted for its duck shooting. “You see, this man is going up in the air over a bay where there are hundreds of ducks on the water. When he is just over them, he will drop a big net and snare every last one. If you’ll stick around a bit, Johnny, you can have a few ducks to take home.”

So Johnny Moore was also a witness of our flights that day. I do not know whether the lack of any ducks to take away with him was a disappointment or not, but I suspect he did not feel compensated by what he saw.

The usual visitors did not come to watch us that day. Nobody imagined we would attempt a flight in such weather, for it was not only blowing hard, but it was also very cold. But just that fact, coupled with the knowledge that winter and its gales would be on top of us almost any time now, made us decide not to postpone the attempt any longer.

My brother climbed into the machine. The motor was started. With a short dash down the runway, the machine lifted into the air and was flying. It was only a flight of twelve seconds, and it was an uncertain, wavy, creeping sort of a flight at best; but it was a real flight at last and not a glide.

Then it was my turn. I had learned a little from watching my brother, but I found the machine pointing upward and downward in jerky undulations. This erratic course was due in part to my utter lack of experience in controlling a flying machine and in part to a new system of controls we had adopted, whereby a slight touch accomplished what a hard jerk or tug made necessary in the past. Naturally, I overdid everything. But I flew for about the same time my brother had.

He tried it again, the minute the men had carried it back to the runway, and added perhaps three or four seconds to the records we had just made. Than, after a few secondary adjustments, I took my seat for the second time. By now I had learned something about the controls, and about how a machine acted during a sustained flight, and I managed to keep in the air for fifty-seven seconds. I couldn’t turn, of course — the hills wouldn’t permit that — but I had no very great difficulty in handling it. When I came down I was eager to have another turn.

But it was getting late now, and we decided to postpone further trials until the next day. The wind had quieted, but it was very cold. In fact, it had been necessary for us to warm ourselves between each flight. Now we carried the machine back to a point near the camp, and stepped back to discuss what had happened.

My brother and I were not excited nor particularly exultant. We had been the first to fly successfully with a machine driven by an engine, but we had expected to be the first. We had known, down in our hearts, that the machine would fly just as it did. The proof was not astonishing to us. We were simply glad, that’s all.

But the men from the life saving station were very excited. Brinkley appeared dazed. Johnny Moore took our flights as a matter of course, and was presumably disappointed because we had snared no ducks.

And then, quite without warning, a puff of wind caught the forward part of the machine and began to tip it. We all rushed forward, but only Daniels was at the front. He caught the plane and clung desperately to it, as though thoroughly aware as were we of the danger of an upset of the frail thing of rods and wings. Upward and upward it lifted, with Daniels clinging to the plane to ballast it. Then, with a convulsive shudder, it tipped backward, dashing the man in against the engine, in a great tangle of cloth and wood and metal. As it turned over, I caught a last glimpse of his legs kicking frantically over the plane’s edge. I’ll confess I never expected to see him alive again.

But he did not even break a bone, although he was bruised from head to foot. When the machine had been pinned down at last, it was almost a complete wreck, necessitating many new parts and days and days of rebuilding. Winter was fairly on top of us, with Christmas only a few days off. We could do no more experimenting that year.

After all, though, it did not matter much. We could build better and stronger and more confidently another year. And we could go back home to Dayton and dream of time and distance and altitude records, and of machines for two or more passengers, and of the practical value of the heavier-than-air machine. For we had accomplished the ambition that stirred us as boys. We had learned to fly.

Leave a Comment