It’s Flight Time! Get Ready for the Incredible Spring Bird Migration

Spring means it is time for the arrival of several billion feathered visitors from Mexico, Central America and South America. Many of these birds make incredible journeys every year to find the perfect place to nest and raise their young in the U.S. and Canada.

The wide variety of migratory birds includes many colorful songbirds: warblers, tanagers, vireos, buntings and orioles, to name a few. Ducks, cranes, shorebirds, raptors and hummingbirds also migrate.

Hundreds of bird species in North America migrate each fall and spring, nesting in the northern part of their range and wintering in the southern. Migration distances vary — from only a few miles up and down a mountain to hundreds or thousands of miles.

A yellow-rumped warbler in flight.

WHY DO BIRDS MIGRATE?

Some species are considered “residents,” such as cardinals, American robins, American goldfinches, chickadees and titmice. They stay in the same location year-round, finding enough food to raise young in the summer to keep them alive during the winter. But the majority of birds migrate because the benefits of migrating outweigh the costs of staying put. There are often better food sources, weather and habitat in the tropics. Species that winter in the U.S. make up for this by having more offspring than those that migrate.

Male indigo bunting

Birds migrate along four major flyways in North America: Pacific, Central, Mississippi and Atlantic. Each spring, most western species travel from Mexico into the U.S. from the tropics. Many eastern species launch from the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico and fly over the Gulf of Mexico to reach the southeastern U.S. Some birds that winter in the tropics fly north through the Caribbean, using the islands as stopovers, until they reach south Florida.

A line of geese fly past a full moon in Northern California.

NIGHT FLIGHTS

Most birds migrate at night, using astronomical cues to help guide them. Also at night, air currents are typically more stable, with no thermal drafts to slow them down. Plus, the birds are less likely to overheat from constant flapping or become food for daytime predators, such as hawks. They use flight calls (different from their songs) to communicate with flockmates so they don’t get separated and also to help each other navigate around obstacles, such as skyscrapers and cell towers.

Birds that cross the Gulf of Mexico fly up to 650 miles in one fell swoop. That amazing voyage might take 18 hours for small songbirds. Leaving in the evening and arriving the next afternoon in the U.S., they’ll stop for food and water before continuing north. Bad weather, including rain and strong headwinds, brings “fallouts.” In these situations, large numbers of exhausted birds will land anywhere they can as soon as they reach shore. Otherwise, a strong tailwind can help push them beyond the coast, and they might continue a while longer until they need to rest and eat.

A pair of rufous hummingbirds along with two female Anna’s hummingbirds at a nectar feeder.

HOW CAN YOU HELP MIGRATING BIRDS?

In addition to climate change and habitat loss, birds face huge obstacles during migration: weather, predators, colliding with glass in buildings, outdoor cats and eating insects sprayed with toxic pesticides.

No wonder numbers have been plummeting for many species over the past century. But you can help! Use UV stickers or screens on windows, keep your kitty inside (or on a leash or in a catio outdoors), plant native plants, use fewer yard chemicals, and provide fresh water and food for birds.

Rose-breasted grosbeak

Spring migration is a fabulous time to go birding. You can try attracting birds to your yard with feeders and baths. This might be the only time during the year that you’ll find certain species. For example, at our home in north Florida, we get rose-breasted grosbeaks only during spring and fall migration. For about a week, they visit our feeders and bird baths, and use the native habitat around our house for rest and protection. Then they’re back on their way to their final destinations.

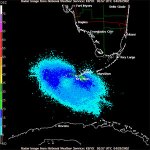

Spring bird migration across the Florida Keys.

On the Radar

There’s a nifty tool scientists use to count numbers of migrating birds in flight: weather radar. That’s right — flocks of birds traveling together are often large enough to see on radar. Using this data, scientists can see how many migrate from Canada/northern U.S. to temperate/subtropical areas of the U.S. (short-distance migration) versus how many migrate from North America to the tropics.

Bats and birds are their specialties, but wildlife biologists Selena Birgit Kiser and Mark Kiser love all species of critters. Both have worked for the State of Florida and previously worked for Bat Conservation International on such programs as the Great Florida Birding and Wildlife Trail and the North American Bat House Research Project.

About ten years ago we were driving from Conway Arkansas to Monroe ga by way of Memphis just before we hit west Memphis we heard this cacophy of noise looked to right of I40…. There were hundreds of thousands or million who knows they were landing on the retention resivours????…in the old rice fields…snow geese we had lucked up on the snow geese migration ..it was amazing….it was a swirling mass landing on the water in waves while other flocks waiting their turns…like hartsfield on a busy day times millions …and just as you enter west Memphis on the left side of I40 a smaller version of migrating ducks looked like wood ducks …that was an amazing day we along with others pulled off the shoulder of I40 and just watched in shock and amazement I have never seen so many animals trying to occupy the same space although black birds would darken the sky when they would harvest rice there ….but this was like agitated storm clouds of snow geese…and no cameras and phones dead….I would love to see it again

This is such an informative and fascinating article! I had no idea that so many bird species migrate such long distances each year. It’s incredible that they are able to find their way back to the same nesting grounds each year, even from thousands of miles away. I also didn’t realize that some bird species are considered “residents” and stay in the same location year-round.

I’m curious about the role of climate change on bird migration patterns. Are there any changes in their behavior or routes due to changes in weather patterns or habitat?

Thank you for sharing such a wonderful article with us. It’s truly amazing to learn about the incredible journeys that these feathered visitors make each year. The illustrations are beautiful as well!